The 50 Least Deserving Oscar Winners Per Industry Insiders, Ranked

The Academy Awards have long been the subject of scrutiny regarding the merit of their selections, particularly when wins appear to be the result of political campaigning rather than artistic superiority. Over nearly a century of ceremonies, several winners in major categories have been retroactively deemed less deserving by industry insiders and critics. These instances often highlight a disconnect between the voting body of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences and the broader cinematic legacy of the nominated films. Factors such as studio influence, sentimental narrative arcs, and the specific historical context of a vote frequently play significant roles in these controversial outcomes. Examining these choices provides a clearer understanding of how the Oscars can occasionally miss the mark on enduring cultural impact.

Alicia Vikander

Alicia Vikander won the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress for her role in ‘The Danish Girl’. Many industry insiders criticized the win due to the fact that her character was arguably the lead of the film, leading to accusations of category fraud. Critics from publications like Variety noted that her performance overshadowed her co-star, yet she was campaigned in the supporting category to increase her chances of winning. This tactical move allowed her to avoid competition in the Best Actress category that year. While her talent was undisputed, the circumstances of the win remains a point of contention among awards historians.

Mira Sorvino

Mira Sorvino took home the Best Supporting Actress Oscar for her performance in ‘Mighty Aphrodite’. While she received praise for her comedic timing as a high-pitched sex worker, many insiders felt the win was a byproduct of the aggressive Miramax campaigning strategies of the mid-1990s. Competing against established veterans, Sorvino’s win was seen as a surprise that did not necessarily translate into a long-standing cinematic legacy. In retrospective discussions, critics often point to this win as an example of how a singular, flashy performance can momentarily capture the Academy’s attention. Her career trajectory following the win is frequently cited in debates about the Oscar curse.

Kim Basinger

Kim Basinger won Best Supporting Actress for ‘L.A. Confidential’, a film that was otherwise overshadowed by the success of ‘Titanic’. Many critics argued that while Basinger was effective in her role, her performance was largely a classic “femme fatale” archetype that did not require significant range. Insiders at the time suggested that the win served as a career achievement award for a popular star rather than an acknowledgment of the year’s most complex performance. Some felt that her co-stars in the same film or other nominees offered more nuanced portrayals. The win remains a classic example of the Academy favoring a glamorous star in a high-profile noir revival.

Cher

Cher received the Best Actress Oscar for ‘Moonstruck’, a win that is often categorized as a sentimental acknowledgment of her career and persona. While ‘Moonstruck’ was a commercial and critical success, many industry experts felt that other nominees, such as Glenn Close in ‘Fatal Attraction’, delivered more transformative performances. The decision was viewed by some as the Academy making up for her previous loss for ‘Mask’. Critics have noted that Cher’s performance, while charming, relied heavily on her established screen presence. This win is frequently debated during discussions about whether the Academy rewards the best performance or the most beloved celebrity.

Elizabeth Taylor

Elizabeth Taylor won the Best Actress trophy for ‘BUtterfield 8’, a film she famously disliked and only appeared in to fulfill a contract. Industry insiders largely believe the win was a “sympathy vote” following Taylor’s near-fatal bout with pneumonia shortly before the ceremony. At the time, even Taylor herself acknowledged that she won because of her health scare rather than the quality of the film or her performance. Critics generally rank ‘BUtterfield 8’ as one of the weaker films in her filmography, noting its melodramatic and dated script. This victory is often cited as the definitive example of external personal circumstances influencing Academy voters.

Charlton Heston

Charlton Heston won Best Actor for the epic ‘Ben-Hur’, a film that dominated the ceremony with a record-setting eleven wins. While the scale of the production was undeniable, many critics argued that Heston’s performance was stiff and lacked the emotional depth seen in other nominees. Insiders suggested that Heston benefited from the overall sweep of the film rather than the individual merit of his acting. Other actors in the category, such as Jack Lemmon in ‘The Apartment’, were considered to have given more complex and enduring performances. Heston’s win is often viewed as a result of the Academy’s historical preference for massive historical epics.

Rex Harrison

Rex Harrison won Best Actor for ‘My Fair Lady’, reprising a role he had already made famous on the Broadway stage. Some industry insiders felt that Harrison was simply “talking his way through” the musical numbers, a technique he perfected but one that lacked traditional vocal range. Critics have pointed out that the performance was more of a recreation of a stage play than a performance tailored for the medium of film. Peter O’Toole’s work in ‘Becket’ that same year is often cited as a more deserving, cinematic portrayal that was overlooked. Harrison’s victory is frequently seen as the Academy rewarding a safe and familiar veteran performance.

John Wayne

John Wayne received the Best Actor Oscar for ‘True Grit’ late in his career, an award many viewed as a lifetime achievement honor. While Wayne was an undisputed icon of American cinema, insiders felt his performance as Rooster Cogburn was a caricature of his own established screen persona. Critics noted that the win came at the expense of younger, more revolutionary performances like those in ‘Midnight Cowboy’. The win was widely interpreted as the Academy honoring the “Old Hollywood” era during a time of significant cultural and cinematic transition. It remains one of the most prominent examples of the Academy rewarding a legend for a mid-tier role.

Art Carney

Art Carney’s Best Actor win for ‘Harry and Tonto’ is frequently cited as one of the biggest upsets in Oscar history. Carney beat out legendary performances by Al Pacino in ‘The Godfather Part II’ and Jack Nicholson in ‘Chinatown’. Industry insiders were shocked that a small, sentimental film about an elderly man and his cat could best two of the most iconic roles in cinema history. The consensus among historians is that the older demographic of the Academy at the time identified more with Carney’s character. This win is often used to illustrate how the Academy can sometimes be out of sync with the lasting cultural importance of specific films.

Renée Zellweger

Renée Zellweger won Best Supporting Actress for ‘Cold Mountain’ after a period of intense campaigning by the studio. While she was a popular actress at the time, many critics found her performance as Ruby Thewes to be overly stylized and distracting due to her forced accent. Insiders noted that the win felt like a consolation prize after she had lost for ‘Bridget Jones’s Diary’ and ‘Chicago’ in previous years. Critics from The New York Times and other outlets suggested that other nominees in the category provided more grounded and authentic performances. Her victory is often discussed as a “make-good” Oscar rather than a merit-based win for that specific role.

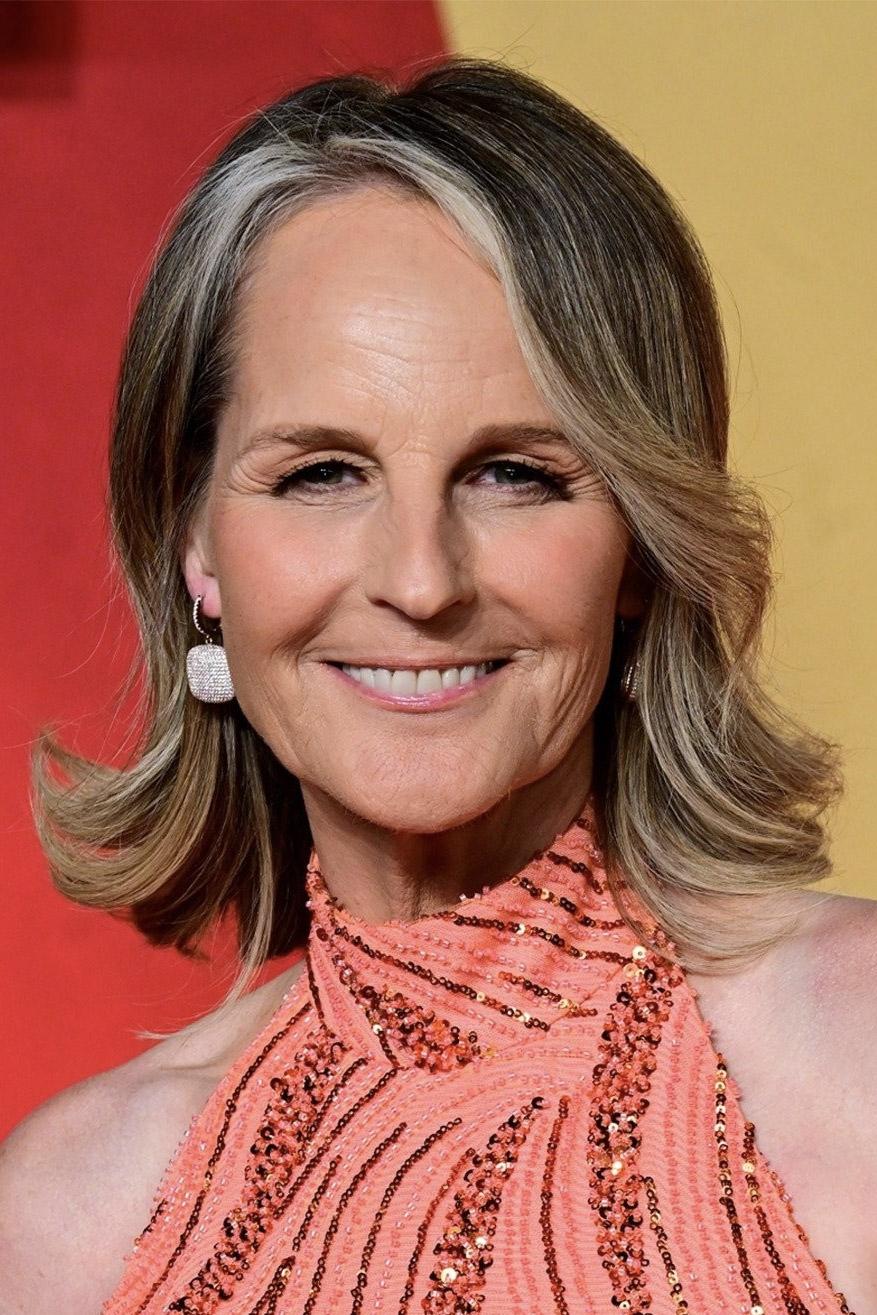

Julia Roberts

Julia Roberts secured the Best Actress Oscar for ‘Erin Brockovich’, a role that leaned heavily on her massive movie-star charisma. While the film was a major hit, many industry insiders felt that the performance did not display the range expected of an Oscar-winning turn. Critics often compared her win to the more transformative work of Ellen Burstyn in ‘Requiem for a Dream’, which was nominated the same year. The narrative of the ceremony seemed focused on Roberts finally winning her “overdue” statue as the world’s biggest female star. This win is often cited as an instance where popularity and box-office clout triumphed over artistic depth.

Jennifer Lawrence

Jennifer Lawrence won Best Actress for ‘Silver Linings Playbook’ at a time when she was the industry’s fastest-rising star. While her performance was well-received, many insiders argued that the role was not as demanding as those of her fellow nominees, such as Emmanuelle Riva in ‘Amour’. The win was seen by some as the Academy’s attempt to crown a new “it girl” who had a relatable public persona. Critics have noted that while Lawrence is a talented actress, this specific win felt rushed and influenced by her immense popularity during the awards season. It remains a point of debate regarding the Academy’s tendency to reward youth and momentum.

Roberto Benigni

Roberto Benigni won Best Actor for ‘Life is Beautiful’, a victory that was accompanied by his famous walk over the seats in the auditorium. While the film was a global phenomenon, many critics and insiders felt the performance was overly manic and sentimental. The win was particularly controversial because he beat out Tom Hanks in ‘Saving Private Ryan’ and Edward Norton in ‘American History X’. Critics from various trade publications suggested that the Academy was charmed by the film’s hopeful message rather than the technical quality of the acting. Benigni’s win is often looked back upon as a product of a specific emotional moment in Hollywood.

Eddie Redmayne

Eddie Redmayne won Best Actor for ‘The Theory of Everything’, portraying physicist Stephen Hawking. While the performance involved significant physical transformation, many industry insiders argued that it leaned heavily on technical mimicry rather than emotional depth. Critics often pointed to Michael Keaton’s performance in ‘Birdman’ as a more inventive and demanding piece of acting that year. Some analysts suggested the Academy favored the biopic format, which has historically been a reliable path to an Oscar. Redmayne’s win is frequently cited in discussions about the Academy’s perceived bias toward roles involving physical disability or well-known historical figures.

Rami Malek

Rami Malek took home the Best Actor Oscar for his portrayal of Freddie Mercury in ‘Bohemian Rhapsody’. Despite the film’s commercial success, it received mixed reviews from critics who found the narrative formulaic and the editing erratic. Insiders noted that Malek’s performance relied heavily on prosthetic teeth and recreations of famous concert footage. Many felt that his win over Christian Bale in ‘Vice’ or Bradley Cooper in ‘A Star is Born’ was a mistake based on the popularity of Queen’s music. The win is often highlighted as an example of the Academy rewarding a high-profile imitation over a complex character study.

Gwyneth Paltrow

Gwyneth Paltrow’s Best Actress win for ‘Shakespeare in Love’ is one of the most famous examples of the Miramax “Oscar machine” at work. Harvey Weinstein’s aggressive marketing campaign is widely credited with securing her the win over Cate Blanchett’s critically acclaimed performance in ‘Elizabeth’. Many insiders felt that Paltrow’s role, while charming, lacked the gravitas and technical difficulty of Blanchett’s portrayal of the English queen. The win sparked long-term debate about the ethics of awards campaigning and the influence of powerful producers on the voting body. Paltrow herself has acknowledged the intense pressure and scrutiny that followed her victory.

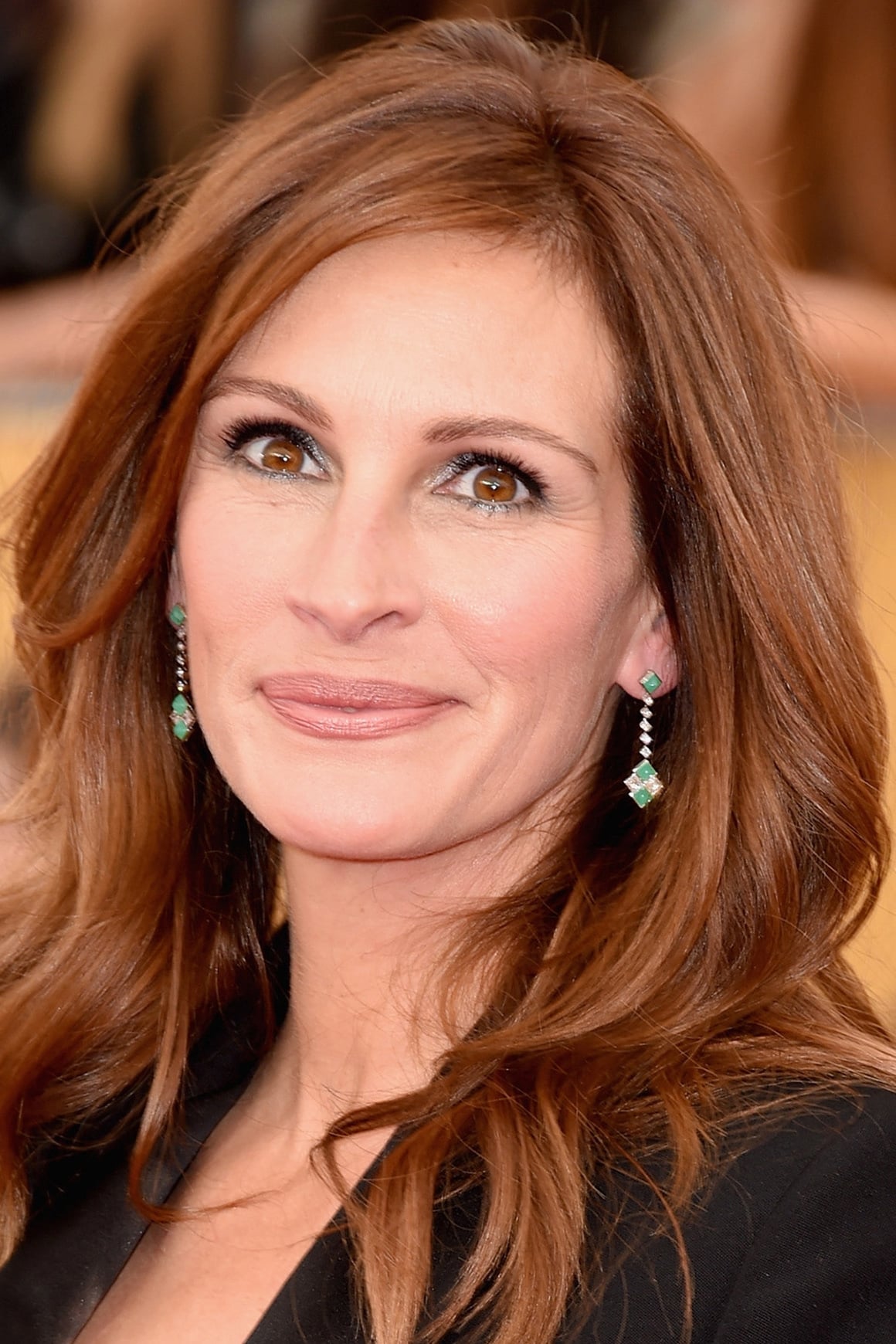

Helen Hunt

Helen Hunt won Best Actress for ‘As Good as It Gets’, a win that surprised many given the competition from veteran actresses. Insiders often point out that Hunt was a television star at the time, and her transition to film was heavily supported by the Academy’s fondness for the romantic comedy genre. Critics argued that her performance, while solid, did not reach the dramatic heights of Judi Dench in ‘Mrs. Brown’ or Helena Bonham Carter in ‘The Wings of the Dove’. The win is frequently viewed as a reflection of the movie’s overall popularity rather than the singular excellence of the acting. It remains a rare instance of a contemporary rom-com leading to a Best Actress win.

Grace Kelly

Grace Kelly won Best Actress for ‘The Country Girl’, an upset victory over Judy Garland’s iconic performance in ‘A Star is Born’. The win was so unexpected that Groucho Marx famously sent Garland a telegram calling it the “biggest robbery since Brinks.” Industry insiders generally agree that Kelly’s win was influenced by her status as Hollywood’s reigning sweetheart and her recent string of successful Hitchcock films. Garland’s performance is now considered one of the greatest in cinema history, while Kelly’s win is often seen as a footnote to her legendary persona. This remains one of the most cited examples of the Academy making the “wrong” choice in hindsight.

Al Pacino

Al Pacino won Best Actor for ‘Scent of a Woman’, a performance characterized by his frequent shouting of the catchphrase “Hoo-ah!” Most industry insiders view this win as a “career Oscar” intended to make up for his previous seven losses for much better films like ‘The Godfather’ and ‘Serpico’. Critics at the time noted that the performance was loud and lacked the nuance of his earlier work. Denzel Washington’s portrayal of ‘Malcolm X’ was widely considered the superior performance that year. Pacino’s win is frequently held up as an example of the Academy’s flawed logic in rewarding an actor for the wrong role at the wrong time.

Sandra Bullock

Sandra Bullock won Best Actress for ‘The Blind Side’, a win that divided critics and industry experts. While the film was a massive box-office hit, many felt the performance was one-dimensional and benefited from the film’s inspirational messaging. Insiders noted that the Academy seemed eager to reward Bullock during a peak in her career, regardless of the role’s complexity. Other nominees, such as Carey Mulligan in ‘An Education’ or Gabourey Sidibe in ‘Precious’, were seen as having delivered more challenging work. Bullock’s win is often cited as a victory for star power and mainstream appeal over artistic merit.

‘The English Patient’ (1996)

‘The English Patient’ won nine Oscars, including Best Picture, but it has since become a punchline for being perceived as dull and overlong. Industry insiders often compare it unfavorably to ‘Fargo’, which was also nominated that year and has had a much more significant cultural legacy. The film was a quintessential Miramax production, benefiting from a massive campaign that emphasized its prestige and epic scale. While beautifully shot, critics argue that its central romance lacks the emotional resonance found in its competitors. Its win is often viewed as the Academy favoring a traditional, sweeping epic over more innovative and dark storytelling.

‘Million Dollar Baby’ (2004)

‘Million Dollar Baby’ won Best Picture in a year that many insiders felt should have belonged to ‘The Aviator’ or ‘Sideways’. Directed by Clint Eastwood, the film was praised for its emotional punch but criticized by some for its manipulative narrative and controversial ending. Critics have pointed out that the Academy often defaults to rewarding Eastwood’s minimalist style, even when other films are more technically or narratively ambitious. The film’s late entry into the awards race created a surge of momentum that some believe blinded voters to its flaws. Over time, the film’s reputation has settled, but the debate over its Best Picture win remains active among film historians.

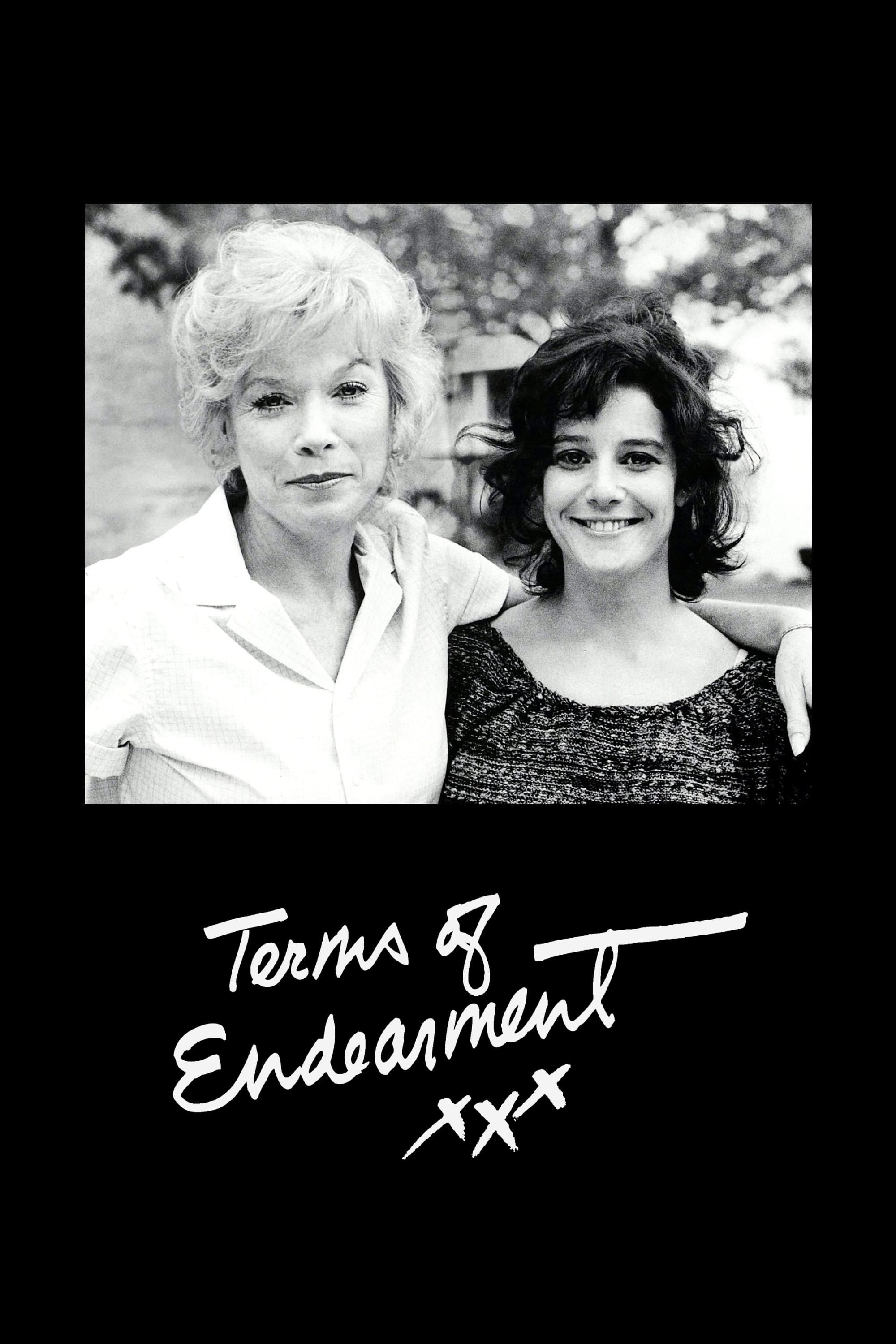

‘Terms of Endearment’ (1983)

‘Terms of Endearment’ is a family dramedy that won Best Picture, beating out the more cinematically significant ‘The Right Stuff’. Industry insiders often criticize the win because ‘The Right Stuff’ was a massive technical achievement that captured a pivotal moment in American history. ‘Terms of Endearment’ was viewed by some as “movie of the week” material that leaned heavily on sentimentality and star power. While the acting was praised, many felt the film’s structure was more suited to television than a Best Picture winner. Its victory is frequently cited as an example of the Academy’s historical bias toward domestic dramas over ambitious, large-scale filmmaking.

‘Oliver!’ (1968)

‘Oliver!’ won Best Picture during a year of radical change in Hollywood, making the choice feel incredibly dated almost immediately. It beat out ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’, a film that is now considered one of the greatest and most influential movies ever made. Insiders view the win as a sign that the Academy was desperately clinging to the traditional musical genre while the industry moved toward “New Hollywood.” Critics have noted that while ‘Oliver!’ is a competent musical, it lacks the vision and technical innovation of Kubrick’s masterpiece. This win is often used to illustrate the Academy’s occasional failure to recognize genre-defining work in the moment.

‘Tom Jones’ (1963)

‘Tom Jones’ won Best Picture as a ribald, experimental comedy that was highly popular at the time but has not aged particularly well. Industry insiders often look back at its win with confusion, as it lacked the gravitas usually associated with the top prize. The film’s frantic editing and fourth-wall-breaking techniques were seen as novel in the 1960s but are now often viewed as distracting. Other nominees that year, such as ‘America America’, were seen by some critics as more substantive works of art. Its victory is frequently attributed to a specific cultural trend in Britain that briefly captivated American voters.

‘A Man for All Seasons’ (1966)

‘A Man for All Seasons’ won Best Picture, a choice that many industry insiders find overly academic and theatrical. The film is a faithful adaptation of a stage play, and critics have argued that it fails to fully utilize the visual language of cinema. While the acting is stellar, the film’s win over ‘Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?’ remains a point of contention among historians. ‘Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?’ was seen as a more daring and visceral exploration of human relationships that pushed the boundaries of the medium. The win for ‘A Man for All Seasons’ is often viewed as the Academy playing it safe with a prestigious, historical subject.

‘An American in Paris’ (1951)

‘An American in Paris’ won Best Picture in an upset over ‘A Streetcar Named Desire’, a film that revolutionized screen acting. Industry insiders often point to this win as an example of the Academy preferring light, colorful entertainment over gritty, transformative drama. While the musical’s dream ballet sequence is legendary, critics argue that the film’s narrative is thin compared to the emotional depth of Tennessee Williams’ adaptation. The win for the MGM musical is seen as a reflection of the studio system’s power at the time. To this day, the loss for ‘A Streetcar Named Desire’ is considered one of the Academy’s greatest oversights.

‘Chariots of Fire’ (1981)

‘Chariots of Fire’ secured the Best Picture Oscar in a surprise victory over ‘Raiders of the Lost Ark’ and ‘Reds’. Many industry insiders felt that the film’s slow pace and traditional narrative were less impressive than the technical mastery of Spielberg’s adventure or the political scale of Warren Beatty’s epic. Critics have noted that the film is most remembered for its electronic score rather than its storytelling. The win was seen by some as a result of a split vote between the two more dominant films in the category. It remains a prime example of a “prestige” film winning over a culture-defining blockbuster.

‘Gandhi’ (1982)

‘Gandhi’ won Best Picture, beating out ‘E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial’ in a move that many insiders still debate. While ‘Gandhi’ was a massive, respectful biopic, critics argued that ‘E.T.’ was a more innovative and emotionally resonant piece of filmmaking. Steven Spielberg’s film went on to become a cultural touchstone, while ‘Gandhi’ is often remembered as a more conventional historical drama. Insiders suggested the Academy felt obligated to reward the serious subject matter of Richard Attenborough’s film over a “family” sci-fi movie. This win is frequently cited when discussing the Academy’s bias against the science fiction and fantasy genres.

‘Gigi’ (1958)

‘Gigi’ won Best Picture and set a then-record by winning all nine of its nominations. However, many industry insiders and critics have since pointed out the film’s problematic themes regarding the grooming of a young woman. Compared to other films of the era, such as ‘Vertigo’—which wasn’t even nominated for Best Picture—’Gigi’ feels like a relic of a dying studio system. Critics argue that its win was more about the spectacle of the production than the quality of its narrative. The film’s legacy has faded significantly, while other films from the same year continue to be studied and celebrated.

‘CODA’ (2021)

‘CODA’ won Best Picture as a late-season surge favorite, but many insiders felt it was a “TV-movie” quality production compared to its competitors. While praised for its representation of the deaf community, critics argued that the narrative was formulaic and predictable. Nominees like ‘The Power of the Dog’ or ‘Drive My Car’ were seen by some as more cinematically ambitious and artistically rigorous. The win was widely interpreted as the Academy wanting a “feel-good” story following the hardships of the global pandemic. Its victory remains controversial among those who believe the Best Picture award should go to the most groundbreaking film of the year.

‘Rocky’ (1976)

‘Rocky’ is a beloved American classic, but its Best Picture win over ‘Taxi Driver’, ‘Network’, and ‘All the President’s Men’ is often criticized by industry insiders. 1976 is considered one of the greatest years in cinema history, and many feel that ‘Rocky’ was the least complex of the four major nominees. Critics have argued that while ‘Rocky’ is an inspiring underdog story, ‘Taxi Driver’ and ‘Network’ were more profound reflections of the American psyche. The win is often seen as the Academy choosing sentimentality and optimism over challenging social commentary. Despite its popularity, the win remains a frequent topic of debate in film circles.

‘Cimarron’ (1931)

‘Cimarron’ was the first Western to win Best Picture, but it is now widely regarded as one of the weakest films to ever hold the title. Industry insiders frequently point to its dated and offensive portrayals of racial groups as a reason for its poor standing in history. Critics have noted that the film’s pacing is erratic and its acting is overly theatrical, even for the early sound era. Many feel that other films from that year have held up much better over time. It is often cited as a win that was more about the film’s scale and ambition at the time than its lasting quality.

‘Argo’ (2012)

‘Argo’ won Best Picture in a year where director Ben Affleck was famously snubbed for a Best Director nomination. Many insiders felt the film’s win was a “sympathy vote” from the Academy to make up for the snub. While a solid thriller, critics argued that films like ‘Zero Dark Thirty’ or ‘Lincoln’ were more substantive and better directed. The film’s historical inaccuracies also drew criticism from those who felt it exaggerated the American role in the rescue at the expense of other nations. Its win is often viewed as a triumph of a Hollywood-centric narrative over more rigorous filmmaking.

‘The Artist’ (2011)

‘The Artist’ won Best Picture as a silent, black-and-white homage to old Hollywood, a premise that many insiders felt was designed specifically to appeal to Oscar voters. While charming, critics argued that the film lacked depth and relied heavily on nostalgia rather than original storytelling. It beat out more contemporary and challenging films like ‘The Tree of Life’ and ‘Moneyball’. Some film historians believe the win was a gimmick that has not aged well in the decade since its release. The film’s success is often cited as a prime example of the Academy’s weakness for movies about the film industry.

‘How Green Was My Valley’ (1941)

‘How Green Was My Valley’ is a well-made drama directed by John Ford, but it is forever overshadowed by the film it beat: ‘Citizen Kane’. Virtually every industry insider and film scholar today considers ‘Citizen Kane’ to be the superior and more influential film. Ford’s film was a safe, sentimental choice that appealed to the Academy’s traditional values at the time. While it is a beautiful movie, it did not change the language of cinema the way Orson Welles’ masterpiece did. This win is frequently cited as the single biggest mistake in the history of the Academy Awards.

‘Ordinary People’ (1980)

‘Ordinary People’ won Best Picture over ‘Raging Bull’, a decision that continues to baffle many industry insiders. While Robert Redford’s directorial debut was a powerful family drama, Martin Scorsese’s ‘Raging Bull’ is now considered one of the greatest films ever made. Critics argue that the Academy’s preference for “prestige” family dramas led them to overlook the visceral power and technical innovation of Scorsese’s work. Over time, ‘Ordinary People’ has remained a respected film, but it does not hold the same cultural or artistic weight as its competitor. This win is often used as evidence of the Academy’s historical hesitation to reward Scorsese.

‘Forrest Gump’ (1994)

‘Forrest Gump’ won Best Picture in a year that many insiders consider the best in modern cinema history. It beat out ‘Pulp Fiction’ and ‘The Shawshank Redemption’, both of which are often ranked higher on greatest-of-all-time lists. Critics have argued that ‘Forrest Gump’ is a sentimental and simplistic look at American history, whereas ‘Pulp Fiction’ was a revolutionary leap forward for independent cinema. The win is seen by some as the Academy choosing a safe, crowd-pleasing narrative over more daring and influential work. Despite its massive box-office success, the film’s win remains a point of intense debate among cinephiles.

‘A Beautiful Mind’ (2001)

‘A Beautiful Mind’ won Best Picture in a year where many insiders felt ‘The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring’ or ‘Gosford Park’ were more deserving. The film was criticized for its significant historical inaccuracies regarding the life of John Nash. Critics often pointed out that the movie followed a standard “Oscar bait” formula of overcoming disability and mental illness. Some felt that the film’s visual representation of schizophrenia was a simplistic Hollywood trope. Its victory is often cited as an example of the Academy favoring a tidy, inspirational biopic over more complex or groundbreaking narratives.

‘Braveheart’ (1995)

‘Braveheart’ won Best Picture in an upset over ‘Babe’ and ‘Apollo 13’, a choice that has faced increased scrutiny over time. Industry insiders often criticize the film for its extreme historical inaccuracies and its heavy-handed direction by Mel Gibson. While a commercial success, critics have pointed out that its narrative is relatively straightforward compared to the technical precision of ‘Apollo 13’. The film’s win is sometimes attributed to the Academy’s love for the traditional “war epic” genre. In hindsight, many feel that the year’s more unique or better-crafted films were overlooked in favor of Gibson’s spectacle.

‘Out of Africa’ (1985)

‘Out of Africa’ is a visually stunning film that won Best Picture, but many industry insiders find it to be slow-moving and lacking in emotional depth. It beat out ‘The Color Purple’ and ‘Witness’, films that critics often argue have more resonant and compelling stories. The film was seen as a classic “Academy favorite” due to its lush cinematography, epic scope, and star power. However, many contemporary critics feel that the central romance lacks chemistry and the film’s perspective is overly colonial. Its win is often categorized as a victory for “prestige” over substance.

‘Dances with Wolves’ (1990)

‘Dances with Wolves’ won Best Picture, famously beating Martin Scorsese’s ‘Goodfellas’. This victory is frequently cited by industry insiders as one of the most egregious examples of the Academy favoring a long, traditional epic over a groundbreaking masterpiece. While Kevin Costner’s film was praised for its scale and its portrayal of Native Americans, ‘Goodfellas’ redefined the crime genre and remains a staple of film education. Critics argue that the Academy’s preference for “westerns” and “epics” led them to make a safe choice. The loss for ‘Goodfellas’ is often discussed as a major turning point in how critics viewed the Academy’s credibility.

‘The King’s Speech’ (2010)

‘The King’s Speech’ won Best Picture over ‘The Social Network’, a decision that many insiders feel has aged poorly. While the film was a well-acted and charming historical drama, ‘The Social Network’ was seen as a definitive film for the 21st century. Critics argued that David Fincher’s direction and Aaron Sorkin’s screenplay were more innovative and culturally relevant. The win was interpreted as the Academy’s older voting base preferring a traditional, royal drama over a fast-paced film about technology and modern society. Today, ‘The Social Network’ is often cited as the more influential and enduring work of the two.

‘Driving Miss Daisy’ (1989)

‘Driving Miss Daisy’ won Best Picture during a year when Spike Lee’s ‘Do the Right Thing’ wasn’t even nominated for the top prize. Industry insiders often criticize the win for its safe and simplified approach to racial relations in America. Critics have noted that the film’s narrative feels regressive compared to the urgent and complex social commentary offered by other films of that era. The win is often used as a prime example of the Academy choosing a comfortable, “feel-good” story over one that challenges the audience. Its legacy has been marred by its perceived lack of depth regarding the serious issues it touches upon.

‘Cavalcade’ (1933)

‘Cavalcade’ is a Best Picture winner that has largely been forgotten by the general public and film historians alike. Industry insiders often point to it as a film that won based on its high production values and patriotic themes rather than its artistic merit. Based on a play by Noël Coward, the film is seen as being overly stagey and lacking in cinematic innovation. Many critics believe that other films from the early 1930s were more deserving of the honor and have had a more lasting impact. It remains one of the least-watched and least-discussed Best Picture winners in the Academy’s history.

‘Around the World in 80 Days’ (1956)

‘Around the World in 80 Days’ won Best Picture in what many insiders consider a triumph of spectacle over storytelling. The film was a massive production with numerous celebrity cameos, but critics have long argued that it lacks a cohesive or compelling narrative. It beat out ‘The Ten Commandments’ and ‘Giant’, both of which are generally regarded as more significant cinematic achievements. The win is often attributed to the showmanship of producer Michael Todd rather than the film’s quality. It is frequently cited as one of the most bloated and least deserving winners in the Academy’s history.

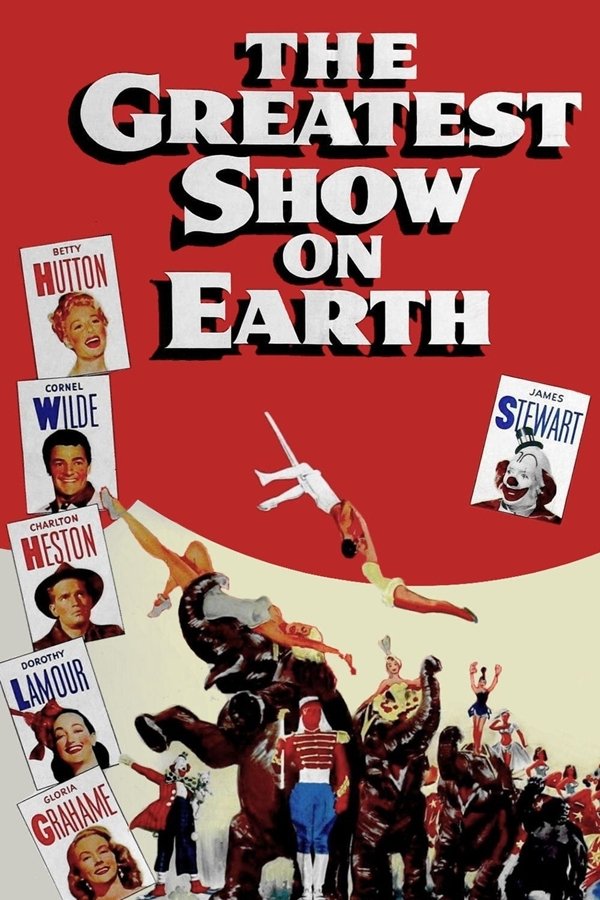

‘The Greatest Show on Earth’ (1952)

‘The Greatest Show on Earth’ is widely considered one of the worst films to ever win Best Picture. Directed by Cecil B. DeMille, it beat out the iconic western ‘High Noon’ and the classic ‘Singin’ in the Rain’—which wasn’t even nominated for Best Picture. Industry insiders believe the win was a “lifetime achievement” award for DeMille rather than a recognition of the film’s quality. Critics have described the film as a long, tedious circus advertisement disguised as a movie. This victory remains a permanent fixture on lists of the Academy’s most embarrassing moments.

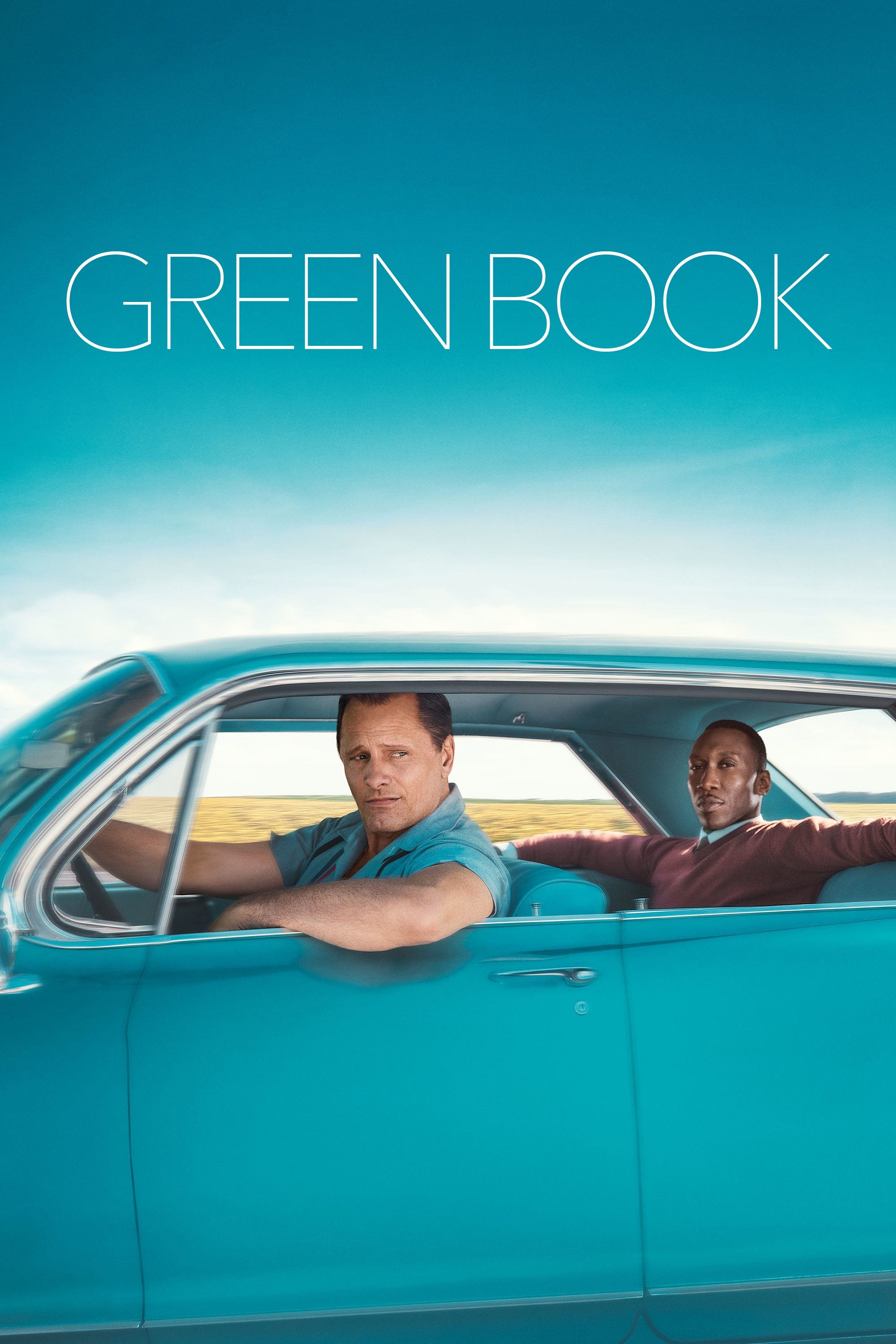

‘Green Book’ (2018)

‘Green Book’ won Best Picture amid significant controversy regarding its portrayal of race and its “white savior” narrative. Many industry insiders and critics from publications like The Atlantic felt that ‘Roma’ or ‘The Favourite’ were superior artistic achievements. The film was also criticized by the family of Dr. Don Shirley, who claimed the movie misrepresented his life and his relationship with Tony Lip. The win was seen by some as a step backward for the Academy after years of efforts to diversify its membership and taste. It remains one of the most divisive Best Picture winners of the modern era.

‘Shakespeare in Love’ (1998)

‘Shakespeare in Love’ secured its Best Picture win through one of the most aggressive and expensive Oscar campaigns in history. Directed at ‘Saving Private Ryan’, the campaign led by Harvey Weinstein successfully convinced voters to favor the romantic comedy over Steven Spielberg’s war epic. Industry insiders often point to this win as the moment the Oscars became as much about marketing as they were about film quality. While a witty and well-made film, many feel it lacks the historical and technical weight of Spielberg’s masterpiece. This win is frequently cited as the ultimate example of how a studio can “buy” an Oscar.

‘Crash’ (2004)

‘Crash’ is frequently ranked by industry insiders and critics as the least deserving Best Picture winner of all time. It famously beat ‘Brokeback Mountain’, a film that was widely expected to win and is now considered a landmark in queer cinema. Critics have slammed ‘Crash’ for its heavy-handed and simplistic approach to racial tensions, using coincidences to drive its plot. Even some members of the cast and crew have since expressed surprise or mixed feelings about the win. This victory is often viewed as the Academy’s failure to recognize a groundbreaking and superior piece of filmmaking in favor of a safe, didactic drama.

Share your thoughts on which Oscar win you find the most controversial in the comments.