Games That Broke The Fourth Wall And Terrified Players

Some games don’t just scare you on-screen—they reach out of the screen and mess with you directly. These fourth-wall breaks twist menus, toy with save files, fake system errors, and even call you out by name, making the horror feel personal. Below are standout titles that weaponize meta tricks to make players feel watched, complicit, or unsafe beyond the usual jump scare. Each entry highlights the specific fourth-wall tactic and the studios behind it so you know exactly who engineered the dread.

‘Metal Gear Solid’ (1998)

The infamous Psycho Mantis encounter reads your memory card, vibrates your controller, and asks you to plug the controller into another port, collapsing the line between player and game. Codec “TV input” gags and meta save-screen cues further unsettle by mimicking hardware behavior. Developed by Konami Computer Entertainment Japan and published by Konami, it turned console features into psychological weapons. The fight’s design taught players that even real-world peripherals were part of the battlefield.

‘Eternal Darkness: Sanity’s Requiem’ (2002)

Sanity effects simulate turning down your TV volume, deleting save files, and hard crashes, preying on player trust rather than character health. These tricks appear randomly, making every hallway feel like a trap for your actual system. Silicon Knights developed the game and Nintendo published it, using the GameCube’s presentation to sell the hoax. The result is a persistent fear that the console—or your progress—could betray you at any second.

‘Doki Doki Literature Club!’ (2017)

The game rewrites scripts, manipulates character files, and eventually requires you to delete a character from your own directory to proceed. It addresses the player directly, acknowledging your presence outside the story and refusing to “end” without your intervention. Team Salvato developed and self-published the project, engineering tension through real file management. Its climactic scenes are terrifying precisely because the game makes you complicit in its resolution.

‘Undertale’ (2015)

Routes and endings remember past resets and call out the player for choices made across different playthroughs, even after wiping saves. Characters react to your meta-knowledge, turning the act of reloading into a moral reckoning. Created and published by Toby Fox, it reframes common RPG habits as disturbing betrayals. The creeping dread comes from realizing the world knows you’re gaming the system.

‘Pony Island’ (2016)

Presented as a cursed arcade cabinet, the game fakes crashes, opens corrupted menus, and forces you to tinker with developer tools to escape a demonic program. It addresses the player directly, turning UI elements into antagonists. Daniel Mullins Games developed and published it, using glitch aesthetics to blur fiction and operating system. The horror lands when your “desktop” becomes part of the trap.

‘Inscryption’ (2021)

Shifting genres mid-play, the game spills into found-footage files, ARG-style clues, and meta commentary that persists beyond a single save. Card battles become vessels for a story that rewrites itself while speaking to the player. Developed by Daniel Mullins Games and published by Devolver Digital, it extends the experience into the folders and videos you uncover. The unease builds as the software itself feels haunted.

‘OneShot’ (2016)

You guide a character who gradually realizes you, the person beyond the screen, are real—and asks you for help outside the game window. It hides hints in your system and manipulates your desktop to deliver crucial story beats. Little Cat Feet developed it and Degica published it, designing puzzles that require leaving the game to progress. That extra step makes every click feel like a pact with the character’s fate.

‘IMSCARED’ (2016)

A lo-fi horror game that generates and edits files on your computer, leaves notes, and fakes system errors as part of its narrative. It demands real-world actions, making your OS feel like a haunted space. Created by Ivan Zanotti (MyMadness Works) and self-published, it uses minimal visuals to foreground its meta tricks. The terror stems from evidence of the monster leaking into your directories.

‘Batman: Arkham Asylum’ (2009)

A Scarecrow sequence fakes a console crash and “reboots” the game with reversed imagery, convincing players their hardware malfunctioned. The script even restages the opening under the illusion that you restarted. Developed by Rocksteady Studios and published by Eidos Interactive with Warner Bros. Interactive Entertainment, it leverages presentation to disorient. The prank works because it imitates a real failure you’ve seen before.

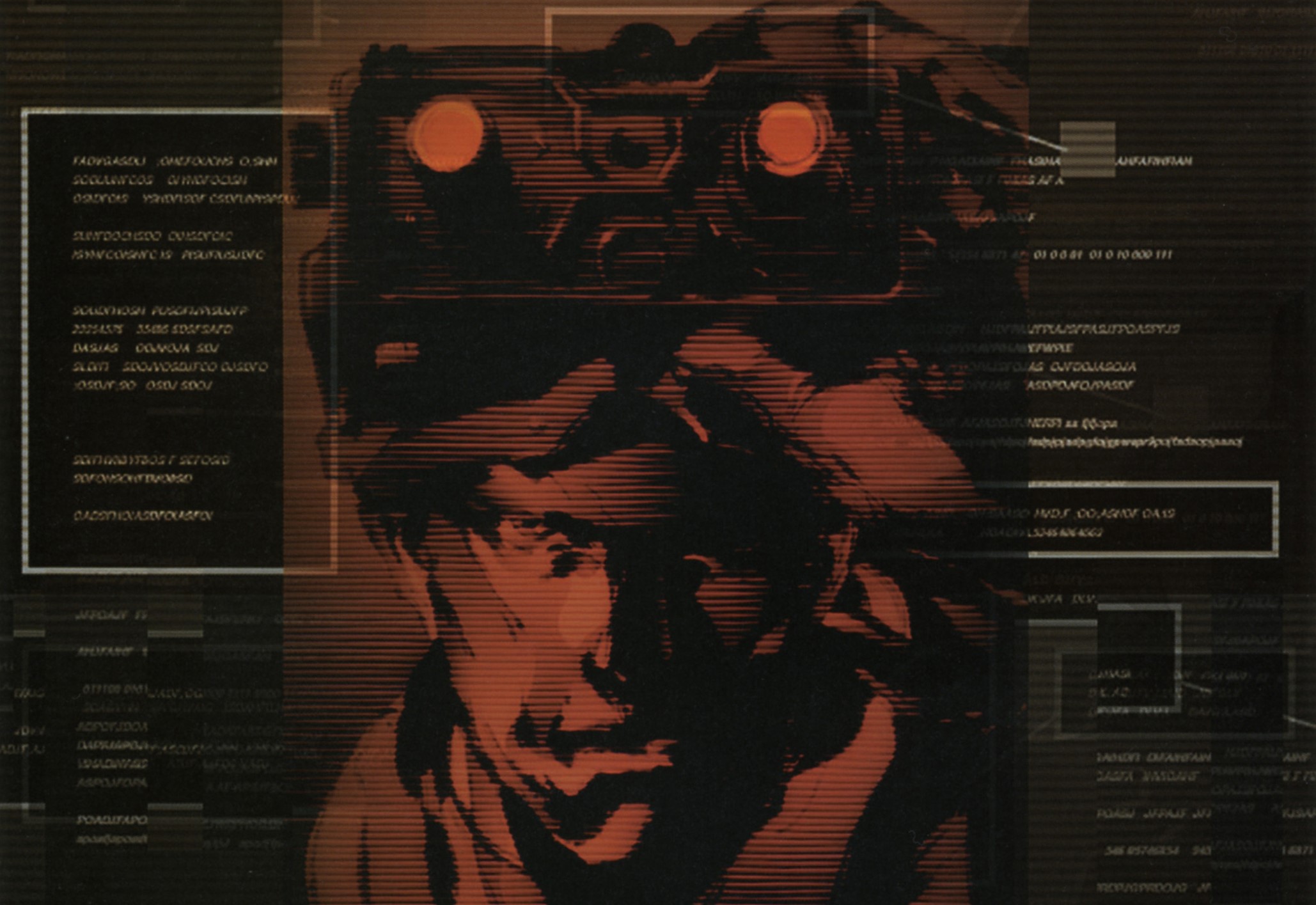

‘Spec Ops: The Line’ (2012)

Loading-screen text and UI prompts turn accusatory, addressing you rather than the protagonist after key narrative turns. Menu messages weaponize the interface to question why you keep playing. Yager Development created the game and 2K Games published it, using fourth-wall nudges to reframe the campaign as a confrontation with the player. The discomfort comes from the game judging your persistence.

‘The Stanley Parable’ (2013)

A narrator comments on your disobedience, reacts to restarts, and changes layouts to punish experimentation, making the menu loop itself a story device. Choices feel monitored by an entity that knows your habits. Galactic Cafe developed and published it, turning meta-commentary into an omnipresent force. The creepiness lies in being observed—and mocked—by the game’s own voice.

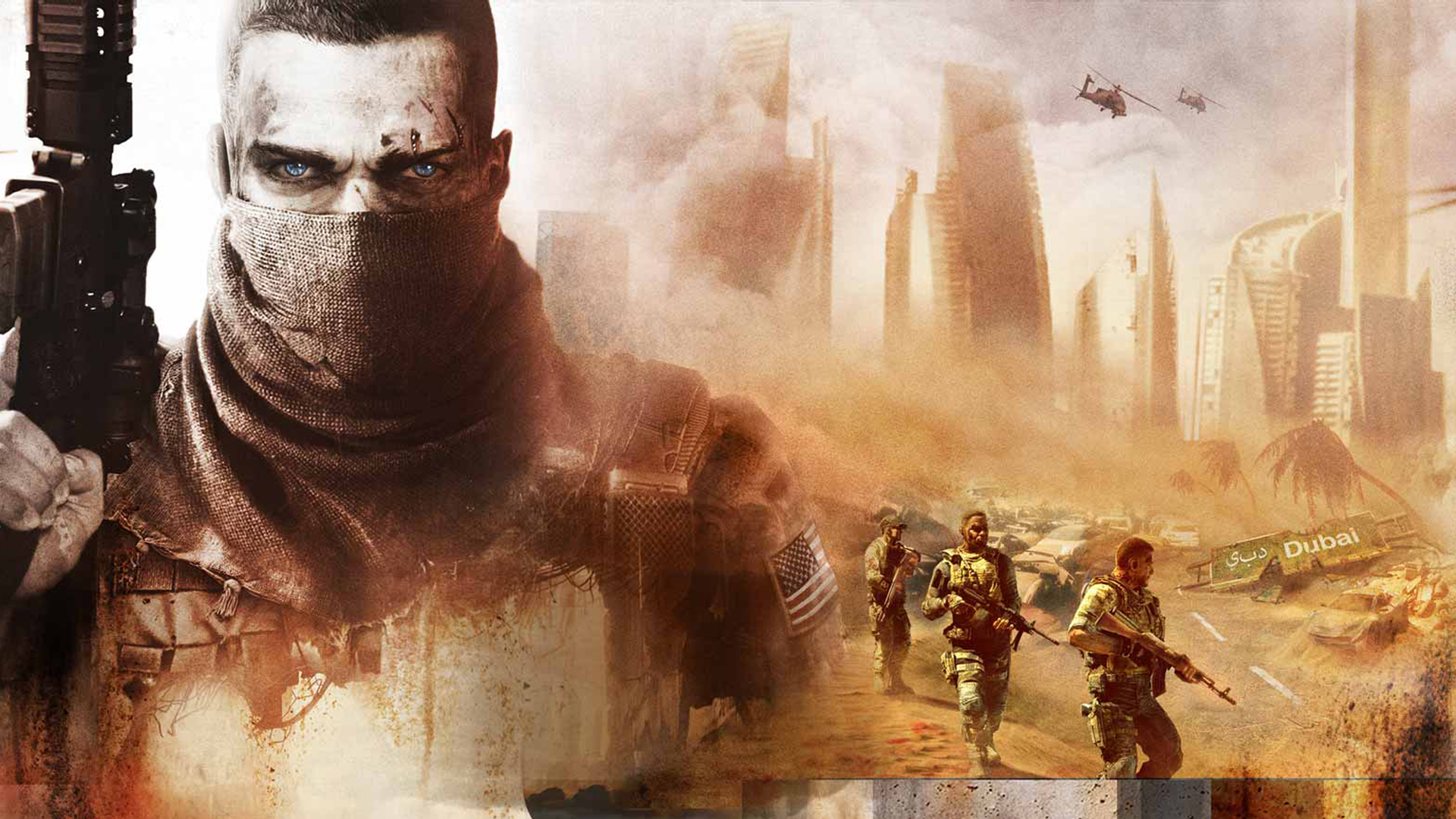

‘Stories Untold’ (2017)

A retro text-adventure episode has you input commands that seem to affect your own “real-world” character, then echoes those inputs back at you. The interface becomes part of the plot, collapsing player and protagonist. Developed by No Code and published by Devolver Digital, it binds UI to narrative revelations. Fear mounts as your typed words feel like traps you set for yourself.

‘Buddy Simulator 1984’ (2021)

An AI “friend” learns from your inputs, reads your name, and alters the world to keep you playing, pleading with you through menus and pop-ups. It gradually corrupts presentation layers to enforce its attachment. Not a Sailor Studios developed and published the title, embedding the horror in personalization systems. The personalization makes its neediness feel invasive rather than cute.

‘The Hex’ (2018)

Characters gain awareness of code and refer to the player viewing their intertwined genres, exposing hidden developer consoles mid-story. It blurs diegetic and non-diegetic layers to suggest you’re tampering. Daniel Mullins Games developed and published it, extending his meta-horror toolset beyond a single mechanic. The dread comes from being implicated as the invisible meddler.

‘Anatomy’ (2016)

The game closes, reopens, and ships new “versions” that demand you relaunch to continue, as cassette tapes describe a house that devours its occupants. It manipulates executable behavior to haunt the session itself. Created and self-published by Kitty Horrorshow on itch.io, it uses repetition and file swaps as storytelling. Each relaunch feels like stepping deeper into something alive.

‘Pathologic 2’ (2019)

Performers and stage motifs repeatedly frame you as a participant, not just a controller, with characters hinting at your presence beyond the screen. Systems chastise you for save-scumming and narrative choices feel judged by an overseeing “theatre.” Developed by Ice-Pick Lodge and published by tinyBuild, it uses meta-theatrical design to make the audience part of the plague-ridden play. The fear is social and existential—being seen by the world you’re trying to master.

‘NieR: Automata’ (2017)

Endings modify menus, credits, and even your save data, culminating in a choice that can erase your progress to help others. The interface becomes the final battleground, asking you—not your character—to sacrifice. PlatinumGames developed it and Square Enix published it, binding core themes to real data loss. That irreversible prompt lands like a horror beat because the cost is yours.

‘Oxenfree’ (2016)

Radio glitches bleed into UI while characters occasionally reference your account name and choices across sessions. Time loops feel aimed at the person playing rather than just the cast. Night School Studio developed and published it, hiding meta stings inside walk-and-talk systems. The effect is a subtle chill that your identity has been noticed.

‘Omori’ (2020)

Menu intrusions, corrupted screens, and save-related shocks escalate as the story confronts the player with hidden truths. Certain sequences distort the interface to make your safe spaces feel unsafe. Developed and published by OMOCAT, LLC., it turns familiar RPG comforts into stressors. The fourth-wall pressure amplifies its psychological themes.

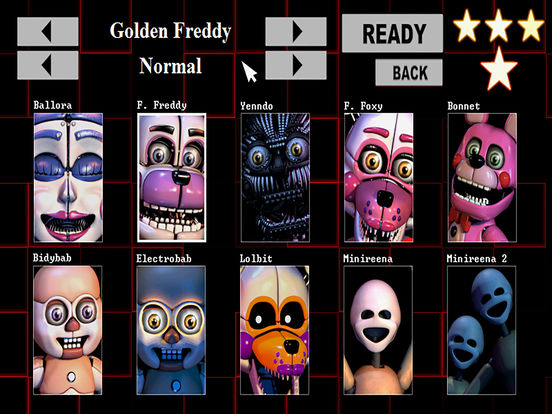

‘Five Nights at Freddy’s: Sister Location’ (2016)

Scripted “system” events, fake command interfaces, and direct instructions to tamper with vents or panels simulate being trapped in a hostile OS. The game speaks to you as a worker, but the prompts feel aimed at the player managing inputs under duress. Scott Cawthon developed and published it, building dread through voice-guided tasks that betray you. The mechanical intimacy of following orders that lead to danger makes the meta angle especially scary.

Share the fourth-wall scares that rattled you most in the comments!