5 Things About ‘Django Unchained’ That Made Zero Sense and 5 Things About It That Made Perfect Sense

Quentin Tarantino’s ‘Django Unchained’ blends spaghetti western style with a brutal snapshot of the antebellum South. It follows an enslaved man who becomes a bounty hunter and sets out to free his wife from a powerful plantation owner. The story moves through towns, camps, and plantations across the American South with a mix of gunfights, schemes, and uneasy alliances.

The film mixes documented practices with bold inventions. Some details line up with period records and social structures while others lean on movie tradition or modern references. Here are five items that strain plausibility and five that match how the world worked at the time.

Zero Sense: Explosives out of time

The film shows bundled sticks of explosive used like common dynamite. Packaged dynamite was not available in the years shown in the story. Nitroglycerin existed but it was unstable and not transported or deployed in neat paper wrapped cartridges with simple fuses that anyone could sling into a house.

Portraying those red sticks as a ready tool simplifies a dangerous chemical reality. The image fits western iconography that audiences recognize, yet the technology seen in those scenes would not have been on hand for men riding through Mississippi during that period.

Perfect Sense: Bounty hunting law

Rewards for wanted criminals were a normal fixture of local law enforcement across states and territories. Notices promised payment for the capture of named offenders and payment could be claimed with a body or clear proof of identity. Sheriffs and courts processed these rewards through documented receipts that confirmed a legal kill or a lawful arrest.

Carrying copies of warrants and naming witnesses protected the claimant from prosecution. The movie’s routine of presenting paperwork, explaining the warrant in front of a crowd, and then collecting a reward mirrors the administrative steps that kept a private manhunter on the right side of a sheriff and a judge.

Zero Sense: Mandingo matches myth

The story centers a plantation economy that treats forced combat between enslaved men as a high dollar spectacle. Historians have not found reliable primary evidence of formal death matches arranged as entertainment in the way shown on screen. The word Mandingo became popular through later fiction such as ‘Mandingo’ and created a durable but shaky pop culture image.

Slaveholders inflicted extreme violence and staged brutal punishments. Men were forced to fight informally at times. Turning that into a luxury gambling pastime with fixed rules and elite spectators reflects a modern myth more than an event documented in ledgers or court testimony from the era.

Perfect Sense: German Texas fits

Large communities of German speakers settled in the Southwest before the war between the states. Towns with German newspapers and businesses were common in parts of Texas. A German trained professional working itinerantly on the frontier is consistent with immigration patterns and trade networks of the time.

Traveling dentists really did operate from wagons and moved town to town offering extractions and false teeth. The cover story of a dentist on the road fits a known occupation that allowed movement across counties and provided a reason to carry tools and cash.

Zero Sense: Hooded riders timing

A hooded night raid appears long before the organization most viewers associate with that look came into existence. The specific costume and its form echo a later era and a recognizable screen image rather than clothing recorded in the time and place of the story.

There were earlier night riders and slave patrols that used masks or simple coverings to hide identity. Those groups enforced curfews, hunted escapees, and terrorized communities. The exact look and coordinated gear in the film read as a later visual that does not match the calendar of the setting.

Perfect Sense: Pseudoscience on plantations

Planters and physicians in the nineteenth century promoted phrenology and other racial theories to justify hierarchy. Measuring skulls and claiming that bone ridges proved character or obedience was presented as learned knowledge in parlors and lecture rooms. These ideas circulated in books, newspapers, and traveling demonstrations.

Using that language to assert mastery gave owners a claim of natural order and a veneer of science. A plantation host showing off such beliefs at a table reflects how fashionable pseudoscience operated as social display and as a tool to rationalize forced labor.

Zero Sense: Armed travel freedom

The film places a Black man on horseback with firearms moving openly through towns. Southern states enforced laws that barred enslaved people and often free Black residents from carrying guns or riding without explicit written permission from a white authority. Penalties included confiscation, fines levied on any white sponsor, and corporal punishment.

Some exceptions existed when a white employer issued papers and took responsibility for the Black worker. The broad tolerance shown by strangers in the film does not match the routine street level enforcement that patrols and constables aimed at Black travelers in public spaces.

Perfect Sense: House servant power

A head servant running the main house often wielded real authority inside a plantation. Duties included controlling access to the owner, directing other servants, and passing orders from the big house to the yard. That position made the person a gatekeeper and a key observer of visitors, money, and schedules.

Written accounts describe household managers who tracked inventories, organized punishments at the owner’s command, and shaped who got to speak to the master. The movie’s depiction of a house servant who sizes up threats and steers events aligns with how that role could operate within the violent structure of a large estate.

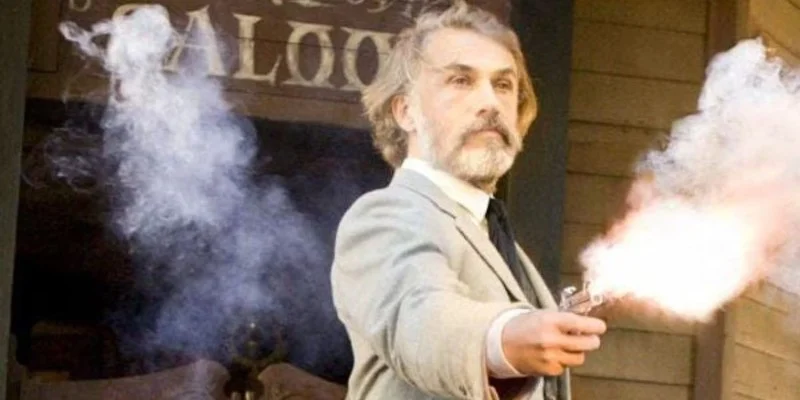

Zero Sense: The handshake shootout

The deal for freedom is completed in a parlor with signatures and payment counted. The sudden killing of the host after the papers change hands immediately endangers everyone present, including the woman whose release depends on leaving the property alive with documents intact. That action guarantees a gun battle in a room crowded with armed men.

Earlier scenes show careful attention to warrants, receipts, and timing to avoid extra bloodshed. Triggering a fight at the moment of legal exit breaks the risk calculations the characters themselves had been following and exposes the mission to needless danger at the worst possible time.

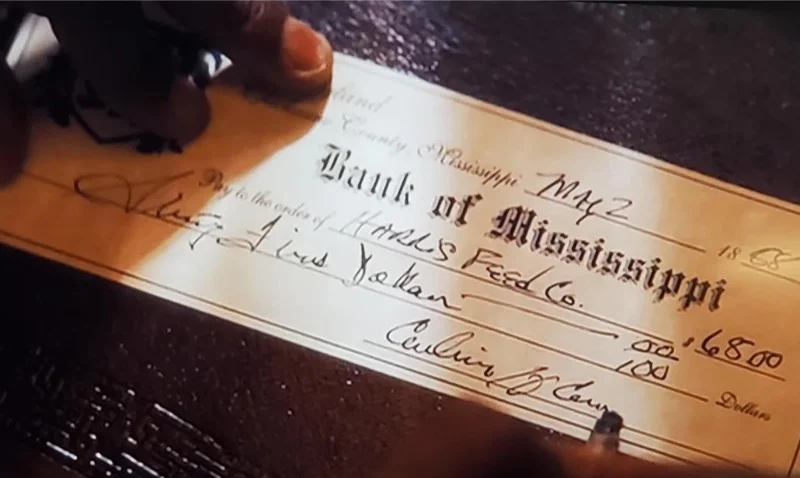

Perfect Sense: Documents and bills

Bills of sale, travel passes, and manumission papers were the backbone of the slave economy’s bureaucracy. A buyer left with notarized documents that named the person purchased and listed marks or scars for identification. Those papers were produced on demand at gates, ferries, and town offices to avoid arrest or seizure.

The plot’s reliance on written proof, signatures, and bills that must be carried away from the plantation reflects how ownership and freedom were recorded. Securing those papers and guarding them on the road mattered as much as the physical escape because the paper trail decided what the law would recognize.

Share the moments you think stretched reality and the details that felt true in ‘Django Unchained’ in the comments.