5 Things About ‘The Prestige’ That Made Zero Sense and 5 Things That Made Perfect Sense

There is a reason people keep revisiting ‘The Prestige’. It packs a full story of obsession, trade secrets, and turn of the century science into a tight mystery that keeps unfolding even after the credits. The plot moves between London theaters and Colorado workshops, switching perspectives through rival journals while showing how stage magic was built, rehearsed, and sold in a booming entertainment scene.

Looking closely at what happens on and off the stage opens up a helpful mix of head scratchers and smartly grounded details. Below are ten focused points that call out where the film stretches plausibility and where it lines up with real practices from the era of gaslight and early electricity. Each item explains what the movie shows along with the historical, technical, or procedural context that clarifies why it either strains belief or fits the world it builds.

Zero Sense: The nightly drown and duplicate routine under the stage

Angier’s show in ‘The Prestige’ uses a trap that drops the performer into a locked water tank while a second Angier appears in the balcony. The production hides a row of tanks beneath the stage and employs a trusted stage engineer to set the cues and the lock. The routine repeats across the run, which means a tank holds a body after each performance while a fresh apparatus resets before the next audience arrives.

Victorian theaters were busy commercial buildings with carpenters, porters, cleaners, fire marshals, and inspectors moving in and out every day. Storing and draining large tanks would leave water trails and smells, and moving bodies required carts, access to alleys, and disposal that survived routine inquests. Even a private theater crew faced limits on waste removal and storage space, so the volume and pace of this operation exceed what most venues and staff could realistically conceal.

Perfect Sense: Borden’s identical twin method for ‘The Transported Man’

Borden’s signature illusion in ‘The Prestige’ uses two men of the same build to execute a clean vanish and reappearance across a short distance. The film shows one brother living publicly as Borden while the other lives as the assistant Fallon, with shared attire, synchronized timing, and mirrored injuries to maintain a continuous identity. The method explains the seamless hat toss, the matching voice, and the instant reentry through a doorway only steps away.

Victorian magic already relied on doubles for quick substitutions, cabinet effects, and mirror gags because audiences sat far enough to miss fine facial differences. Wigs, false beards, and dental veneers served as standard tools, and performers built entire acts around split identities so rehearsal routines and living arrangements protected the secret. The twin solution matches documented practices where a concealed partner or lookalike delivered speed and smoothness that mechanical devices could not reliably achieve on nightly schedules.

Zero Sense: A custom electrical machine built in Colorado and staged in London without practical hurdles

In ‘The Prestige’, Angier commissions an experimental device from Tesla’s Colorado workshop and then uses the machine to power showy stage effects back in London. The story compresses design, fabrication, and transatlantic shipping into a brief window while implying a seamless installation in a city theater. The apparatus features large coils, exposed conductors, and dramatic discharges that start working on cue as soon as it arrives.

Moving heavy electrical gear at the turn of the century required crating, rail transfer to an eastern port, transoceanic shipping, customs clearance, and cartage to a London venue with its own supply limitations. Theaters in that era were still transitioning from gas to electricity, and many sites did not furnish the stable alternating current and floor loading needed for tall coils and transformers. Coordinating power, ventilation, and fire precautions for a new machine would take significant time and paperwork before the first paying audience saw a spark.

Perfect Sense: Trade secrecy through coded journals and withheld keywords

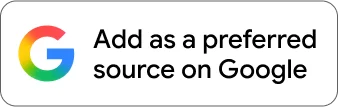

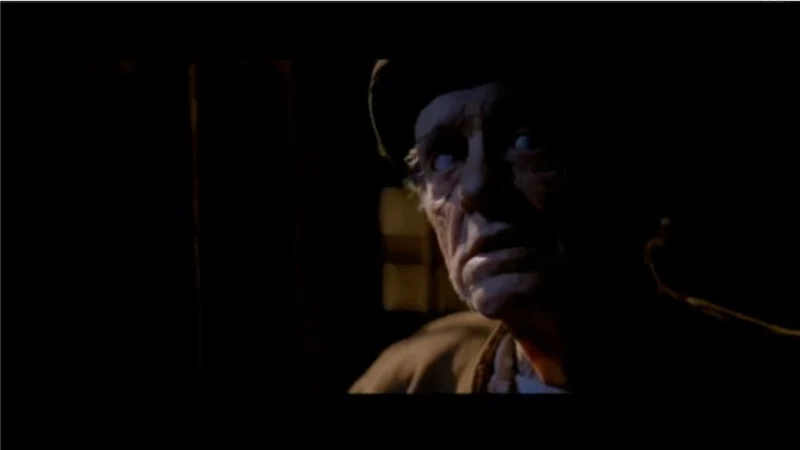

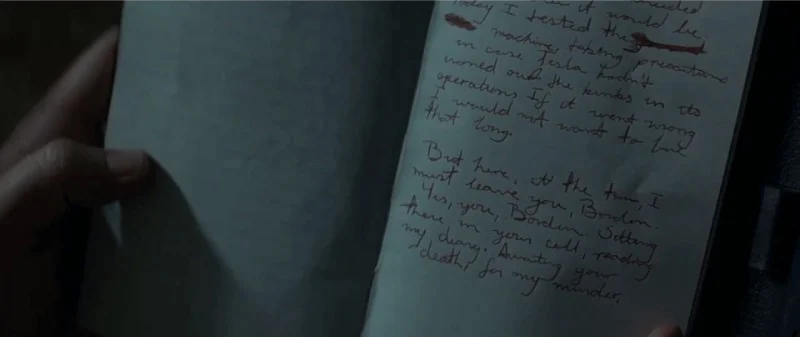

Both magicians in ‘The Prestige’ write technical notes in private journals that only make sense with a missing keyword. The film shows rivals stealing and reading entries that offer real details mixed with traps that waste time, such as sending a competitor to another continent before revealing the ruse. The structure of these diaries keeps methods compartmentalized so assistants learn procedures without gaining the core principle that unlocks an illusion.

Magicians protected livelihoods by splitting knowledge across codebooks, ciphers, and oral instructions, and many used simple letter shifts or keyed phrases to guard workshop notes. Builders and performers also adopted need to know rules where a stagehand learned only the cue sequence he executed and never the final explanation. Using a keyworded diary matches professional habits that balanced documentation with secrecy so an act could be rehearsed while a stolen notebook remained frustrating without the missing key.

Zero Sense: A capital conviction built on a single stage incident and auctioned secrets

‘The Prestige’ shows Borden arrested after a backstage accident where Angier is found dead in a locked water tank. The police focus on the presence of a rival under the stage and a suspicious apparatus owned by the deceased performer. The court rapidly reaches a verdict that leads to a death sentence while the victim’s estate prepares to sell the show’s assets, including intellectual property.

Homicide cases in that period depended on inquests, witness depositions, and expert testimony about cause of death, especially when a mechanism with locks and trapdoors was designed to mimic danger. Valuing and transferring show property also required inventories, bills of sale, and notices, and the idea that a condemned prisoner’s creative rights could be bundled and auctioned within days simplifies procedures. The speed and clarity of these legal and commercial steps compress processes that usually involved extended documentation and review.

Perfect Sense: Risky illusions like the vanishing birdcage and the bullet catch reflect real stage history

‘The Prestige’ includes illusions where a birdcage collapses and vanishes during a flourish, and a bullet catch demonstration goes wrong after tampering. The bird sequence highlights how an animal can be sacrificed by a hidden mechanism, and the bullet scene shows that a single swapped component can turn a controlled stunt into an injury. These moments demonstrate the genuine hazards behind seemingly harmless stage acts.

Historical records show that compact cages, spring steel frames, and pull loops allowed rapid vanish effects that left performers with bruised wrists and occasional animal harm. The bullet catch existed in multiple versions that used wax bullets, sleight of hand, or barrel blocking, yet it carried a reputation for accidents when assistants altered props or misread cues. The film’s treatment of these tricks aligns with known methods and the safety margin that shrinks once sabotage or miscommunication enters the routine.

Zero Sense: Hiring blind stagehands to hide a lethal device during nightly resets

Angier’s production in ‘The Prestige’ employs blind stagehands so no one can report what they see when the water tank and trap system reset after each show. The plan relies on the idea that workers who cannot see will move heavy equipment by feel while remaining unaware of its true purpose. The same crew loads and secures a life endangering apparatus beneath a busy stage every night.

Stage operations in large venues depended on speed, accuracy, and coordination in cramped wings and fly towers, and crews used hand signals, chalk marks, and visual checks to keep people safe. Moving big tanks and locking them into position without sight increases risk of crushed fingers, misaligned lids, and missed latches, which is the kind of error chain theaters tried hard to prevent. A production company would normally spread tasks across trusted workers with eyesight and a foreman to double check placements before the curtain rose.

Perfect Sense: The dedicated engineer figure explains the machinery, cues, and contingencies

Cutter in ‘The Prestige’ serves as designer and chief technician who translates ideas into workable apparatus, supervises rehearsals, and sets emergency protocols. He inspects locks, tests fall distances, and rehearses assistants until cues hit identical marks from show to show. His role bridges creative concept and safe execution by turning an effect into a repeatable routine that can survive tours and new venues.

Nineteenth century magic thrived on specialist builders and fixers who drafted joinery plans, managed metalwork, and tuned weights and springs for travel. Companies kept these experts on retainer to adapt illusions to different stages, adjust for ceiling height, and account for trap placement so the rhythm of an act stayed intact. Presenting a named engineer mirrors how real troupes operated when reliability mattered more than novelty once a marquee trick started selling tickets.

Zero Sense: An unresolved knot choice followed by limited inquiry after a fatal tank escape

Early in ‘The Prestige’, a water tank escape fails and Julia drowns after a disputed knot is tied. The company continues working without a definitive resolution because no one can prove which knot held during the trick. The lack of a settled answer becomes a private feud rather than a matter of record.

In practice, deaths during performances triggered coroner involvement and testimony from crew members about rehearsals, knots, and safety releases. Theaters faced insurance considerations and reputational fallout that pushed managers to document procedures and modify equipment before returning to similar stunts. The film captures the emotional aftermath but downplays the formal steps that would usually follow a public fatality during a stage illusion.

Perfect Sense: Nested diaries and intercut timelines match a period friendly storytelling device

‘The Prestige’ is structured around two journals that characters read in different places and times, which lets the film jump from a prison cell to London workshops to Colorado experiments. The entries move the plot through discoveries and deceptions while delivering technical details and personal motives in the characters’ own words. This framework makes room for method explanations without stopping the story.

Epistolary storytelling was common in nineteenth century literature and transitions smoothly to screen when a narrative needs parallel viewpoints. Using journals to shuttle between timelines matches the habits of the period and gives the audience direct access to trade notes, travel logs, and confessions that feel authentic to the era. The structure provides a practical way to reveal secrets at controlled moments while keeping each timeline anchored to a physical document.

Share your take in the comments about which moments in ‘The Prestige’ you think landed perfectly and which ones still leave you puzzled.