10 Things You (Probably) Didn’t Know About The Godfather

There is a reason people still talk about ‘The Godfather’ after all these years. The story sits at the center of film history, but the way it came together behind the scenes is just as gripping. The production moved fast, solved problems in unusual ways, and left behind details that reward a closer look.

From last minute on set choices to industry controversies, the film’s journey is packed with discoveries. These facts go beyond trivia and explain how specific decisions shaped what ended up on screen. If you love the movie, you will appreciate how much craft and coordination it took to make it feel so effortless.

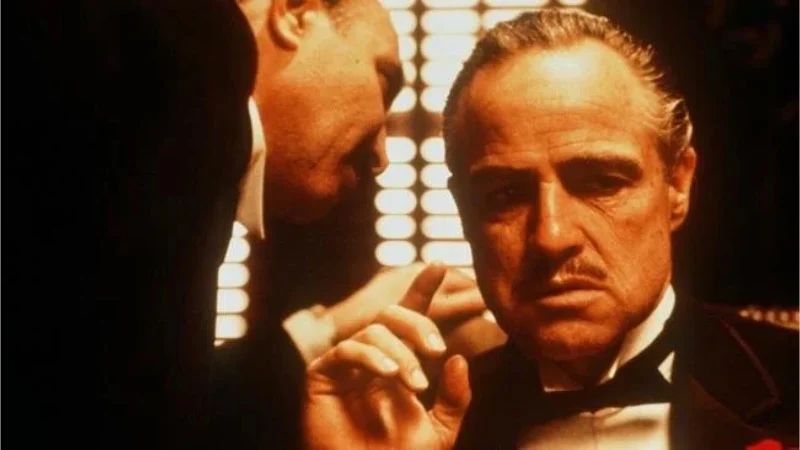

The purring cat in the opening scene was an unplanned addition

The cat in Vito Corleone’s office was a stray found on the lot and handed to Marlon Brando moments before cameras rolled. The animal settled on his lap without rehearsal and started purring loudly, which softened the character’s introduction while keeping the scene’s tension. Because the purring overpowered the dialogue, the team had to loop parts of Brando’s lines later to get clean audio.

That simple choice affected how the scene plays. The pet gave Brando’s hands natural business and created a contrast with the threats in the room. It also meant the camera and sound crew had to adapt quickly since no one expected a live animal to be in the shot when they blocked the scene that morning.

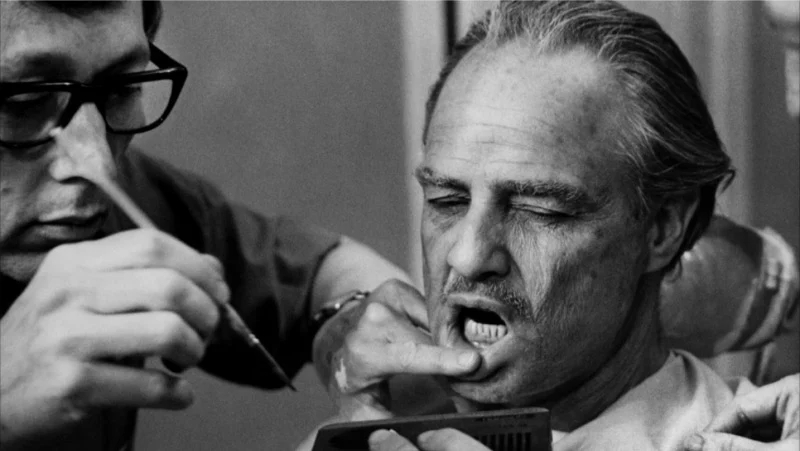

Brando used a custom mouthpiece, not cotton, to shape Vito’s voice

For his screen test, Brando famously stuffed his cheeks with cotton to imagine Vito as a bulldog. Once he won the role, a dental prosthetic was crafted so he could deliver lines clearly while keeping the same look. The appliance pushed his cheeks outward and lowered his jaw, which helped create the distinctive voice and presence.

The mouthpiece let him stay consistent across long shooting days. Makeup and sound teams planned around it so lip movements and diction remained stable from setup to setup. The piece also allowed Brando to remove it between takes to rest his jaw without breaking continuity.

The horse head in the bed was real and came from a rendering plant

The production acquired a genuine horse head from an animal byproducts supplier that worked with slaughterhouses. The prop department cleaned and prepared it for the scene, then coordinated with the set decorators to hide it under the sheets so it would read on camera when revealed.

To capture authentic reactions, the crew set the head right before filming and kept the set tightly controlled. The effect relied on makeup blood, careful placement, and quick resets, since the prop could not sit under hot lights for long. The scene’s shock value came from practical staging rather than camera tricks.

Oranges appear repeatedly before moments of danger

Oranges show up throughout the film ahead of pivotal events. You see them in the market during the attempt on Vito’s life, on the table during tense meetings, and in Vito’s hands in the garden near the end. The fruit’s bright color draws the eye and creates a quiet link between scenes.

The recurring prop use came from a mix of set dressing choices and continuity planning. Once the pattern emerged during shooting, the art department kept placing oranges where they would stand out without distracting from the actors. The result is a subtle visual thread audiences can track across the story.

Nino Rota’s original score nomination was revoked for prior reuse

Composer Nino Rota was initially nominated for Best Original Score for ‘The Godfather’. The Academy later discovered that a key theme had appeared in his earlier work on ‘Fortunella’, which violated originality rules at the time. The nomination was withdrawn after the review process confirmed the reuse.

Rota returned for ‘The Godfather Part II’ with new material and won the award for that film. The episode became a reference point for how the Academy handles themes that carry over from a composer’s previous projects. It also shows how a melody can become iconic even if it existed in another context first.

Gordon Willis pushed low light photography to new places

Cinematographer Gordon Willis lit many interiors with strong top lights and deep shadows to match the story’s mood. He exposed the negative conservatively and protected highlights, which kept faces partially obscured and backgrounds rich. Studio executives worried that audiences would not accept scenes that dark, but the approach stayed in place and defined the film’s look.

Maintaining that style took careful coordination with the lab and camera department. The team tracked light levels with precision and tested stocks to ensure skin tones held detail. Because the sets were dressed for shadow, art and wardrobe departments selected materials that read well when most of the frame sat in low key.

Al Pacino nearly lost the role during early shooting

Paramount executives had concerns about the dailies in the first weeks and considered replacing Al Pacino. The performance did not yet include Michael’s later transformation, so the footage looked understated on its own. Francis Ford Coppola argued that the arc needed time and asked to stage the restaurant scene to prove the casting choice.

After the restaurant sequence was filmed and screened, the atmosphere changed. The calm buildup, the bathroom retrieval, and the precise exit convinced decision makers that Pacino’s take would pay off. The schedule then locked around Michael’s key beats so the character’s progression stayed clear.

The script avoided saying the words Mafia and Cosa Nostra

Community groups negotiated with the producers during pre production and asked for changes to language in the script. The final draft removed or reduced direct references to Mafia and Cosa Nostra, which shifted emphasis toward family names and business fronts. The story stayed the same, but dialogue and signage were adjusted to reflect the agreement.

Those edits required updates to props and set dressing so background text matched the new approach. Legal and publicity teams also reviewed marketing materials to keep messaging consistent. The outcome shaped how characters describe their world without altering the plot’s structure.

The tollbooth ambush used a record number of squibs for its time

The team covered James Caan with a heavy rig of small explosive squibs and blood packs to stage the tollbooth hit. Multiple cameras rolled at once so they could capture the full impact without repeating the most destructive beats. The stunt team planned the timings down to fractions of a second so the blasts looked chaotic but remained safe.

The car, costume, and set pieces were pre weakened to shred on cue. Special effects technicians wired the booth and the surrounding barriers, then synchronized cues with the actor’s movements. Because resetting the rig took a long time, the crew rehearsed extensively to get the main take right.

The Sicilian locations were Savoca and Forza d’Agrò, not the town of Corleone

When the production scouted in Sicily, the real town of Corleone had grown too modern for the period setting. The crew selected Savoca and Forza d’Agrò for their stone streets, hillside views, and intact architecture that matched the story’s timeline. Bar Vitelli in Savoca became a recognizable landmark and still bears the name.

Local residents joined as extras and helped with logistics, including access to courtyards and rural roads. The unit worked with municipal offices to manage traffic holds and protect historic structures during filming. Those choices gave the Sicily chapters a grounded texture that contrasts with the New York material.

Share your favorite hidden detail about ‘The Godfather’ in the comments and tell us which behind the scenes story surprised you the most.