Top 15 Practical Special Effects in Movies

There is something special about effects that are built, lit, and performed right in front of a camera. Miniatures, makeup, animatronics, pyrotechnics, and clever camera tricks have shaped entire worlds without relying on fully digital images. These techniques demand planning and precision, and they leave behind a trail of craftsmanship that you can trace through behind the scenes photos, shop notes, and set blueprints.

This list highlights practical methods that solved specific storytelling problems with hands on engineering. You will find mirror tricks that merge miniatures with live actors, full scale creatures driven by cables and hydraulics, and rotating rooms that let gravity do the work. Each entry explains what was built, how it was filmed, and why the approach delivered what the story needed on the day.

‘Metropolis’ (1927)

The production combined live action with large scale miniatures using the Schüfftan process. Technicians placed precisely angled mirrors in front of the camera to reflect model cityscapes while clear sections in the mirrors let actors appear inside the same frame. This allowed complex in camera composites decades before standard optical printers became common.

The crew also used multiple passes through the camera with careful masking to add lights and signage to the miniatures. Model builders finished surfaces with textured paints so the sets would read at scale under strong studio lamps, and cinematographers controlled depth of field to keep both actors and models sharp enough for the illusion to hold.

‘King Kong’ (1933)

Stop motion animator Willis O’Brien brought Kong to life with armatured puppets covered in foam and fur. The team shot the puppets one frame at a time on miniature sets and combined them with live actors through rear projection and traveling mattes. Each move had to be incremental and consistent to keep motion smooth across thousands of frames.

To integrate foreground and background plates, artists matched lighting direction and contrast so the puppet and projection blended on set. Miniature foliage and dust were added in front of the puppet to sell scale, and careful camera spacing helped keep the rear projection grain aligned with the photographed puppet pass.

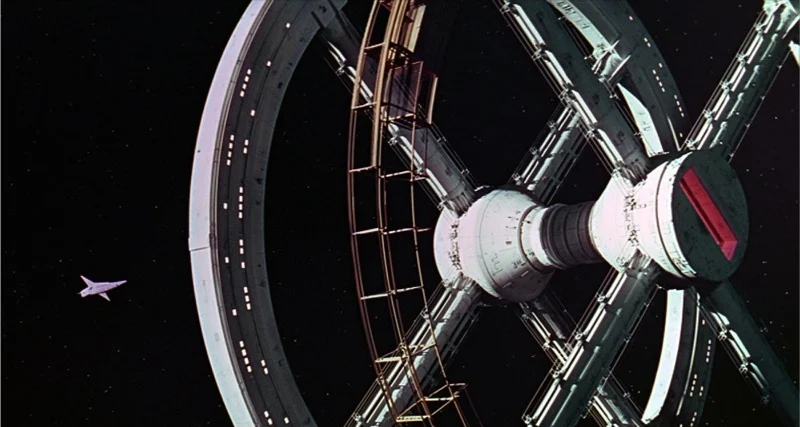

‘2001’ (1968)

The film’s prehistoric vistas used front projection with a reflective screen made from microscopic glass beads. High resolution slides of African landscapes were projected from a position close to the camera, and the screen bounced the light straight back, placing actors and props cleanly against the image without visible spill. This kept backgrounds crisp while preserving natural shadows on the foreground.

The stargate sequence used slit scan photography built by Douglas Trumbull. A long exposure camera moved past a narrow slit of light while artwork slid behind it on motorized tracks. The method created continuously evolving patterns in camera, and variable speed controls let the crew tune the motion during the shoot.

‘The Exorcist’ (1973)

The bedroom set was refrigerated to show actors’ breath on camera, and a mechanical rig shook the bed in controllable increments for repeated takes. Makeup appliances created lesions and discoloration, and a rotating head effect was achieved with an articulated dummy built to match the performer’s proportions.

For the projectile vomit gag, the team loaded pea soup into a pressurized tube hidden in the effect performer’s mouthpiece and aimed the stream with a concealed nozzle. The shot relied on precise cues and consistent pump pressure so the material would hit the mark and remain safe for everyone in frame.

‘Jaws’ (1975)

Special effects crews built three full size mechanical sharks with different configurations for surface and profile shots. The saltwater environment caused frequent failures, so technicians revised seals, hoses, and air bladders to keep the rigs working through long days. The sharks ran on pneumatic and hydraulic systems, with operators coordinating jaw movement, roll, and speed.

To suggest the shark without showing it, the production rigged barrels, blood bags, and tow lines that could be driven by boats just off camera. Practical splashes and drag effects told the audience where the animal was in the water, and these cues were designed to match the mechanics for continuity when the shark did appear.

‘Star Wars’ (1977)

Miniature spacecraft flew through model star fields using motion control passes on the Dykstraflex system. The computer repeated the same camera move multiple times so the crew could photograph separate lighting elements and combine them in optical printing. Surface detailing on the models used kit bashing parts to break up shapes and catch highlights.

Explosions for space battles came from pyrotechnic charges set off on scaled sections of miniature ships. High speed cameras captured debris movement that read as large mass, and black velvet stages minimized bounce light. The team tracked lens choices and camera distances so shots could intercut while preserving perceived scale.

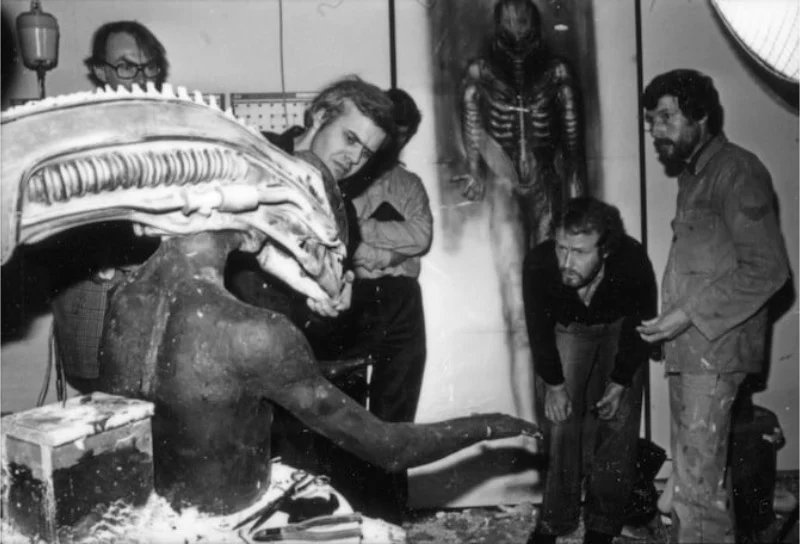

‘Alien’ (1979)

The chestburster sequence used a prosthetic torso built over the actor with concealed blood lines and a breakaway wound. Compressed air and pumps forced the creature puppet through the opening on a timed cue, and the set was protected with coverings that could be reset quickly between takes. Animal organs added texture to the shot under strong key light.

Other creature moments used suit work combined with dripping lubricants and smoke to give the surfaces a wet sheen on camera. The art department selected materials that caught light without revealing seams, and cinematography kept backgrounds dark so the creature edges would stay credible at full size.

‘An American Werewolf in London’ (1981)

Rick Baker’s team staged the transformation with mechanical facial extensions, cable pulls, and bladder inflation under foam latex appliances. The makeup pieces were swapped in a planned sequence so limbs and features could appear to elongate as the scene progressed. Hair growth was created by pulling hair back through skin prosthetics and then reversing the footage.

Hands and feet extended using articulated inserts mounted on plates that matched the actor’s skin tone under the set lighting. The camera held on medium frames to hide off screen operators, and the sound stage floor supported hidden tie downs that stabilized rigs as performers leaned into the effect.

‘Raiders of the Lost Ark’ (1981)

The opening boulder was a large fiberglass shell rolled along a guided track with safety stops. Grip teams timed the roll with the camera dolly to control speed and distance while the actor ran. Close passes were blocked with rehearsed marks that kept the performer out of the boulder’s true path.

The face melting finale used layered gelatin and wax sculptures placed over life casts. Heat guns and hot lights softened the layers in real time, and the crew photographed the process at a slightly higher speed so the deformation looked heavier on playback. Blood and smoke elements were added practically to sell internal pressure and heat.

‘The Thing’ (1982)

Rob Bottin’s shop built complex puppets with cable control, bladders, and breakaway sections that could morph mid shot. Materials like foam latex, gelatin, and methylcellulose created stretching skin and viscous slime. Pneumatics and hand rods allowed tentacles and jaws to open and split on cue while hidden operators synchronized motion.

Effects were staged with smoke, backlight, and chilled air so breath and steam were visible in frame. Shots were planned to allow practical resets, with duplicate skins and cores ready to swap between takes. Blood lines were rerouted through the set floor, and the art department prepared heat resistant pieces for flamethrower interaction.

‘Aliens’ (1986)

The alien queen was a large puppet suspended from a crane rig and operated by a team of puppeteers through cables and hydraulic assists. Jaw, tongue, and head movements were driven independently so performance could be timed to dialogue. The warrior drones used suit performers with elongated headpieces and tail supports to keep silhouettes consistent.

The power loader fight combined a full scale prop worn by the actor with miniature set extensions. Rods and cables were later painted out on the negative by optical means, and the loader arms were counterweighted so the performer could move them smoothly for long takes. Smoke and practical sparks completed the interaction between the machines.

‘Terminator 2’ (1991)

Stan Winston’s crew built animatronic Arnold Schwarzenegger heads and torsos for surgery and damage shots. The mirror scene used a real wall opening dressed as a mirror frame, with the live actor on one side and a puppeteered bust on the other. A performer related to the lead matched movements in the background to complete the illusion.

Bullet impacts on the T 1000 were achieved with practical appliances that opened in flower petal shapes. Pull cables under the costume allowed the petals to snap open on cue, and mercury like textures were added with reflective finishes under controlled lighting. These on set elements intercut with computer generated moments in the same sequence.

‘Jurassic Park’ (1993)

Full scale animatronics for the tyrannosaur and the raptors were built on motion bases with servo and hydraulic control. Skin sections were cast in foam latex and painted to read at scale under rain and key lights. The tyrannosaur rig required recalibration when water weight changed response during night shoots, so operators adjusted timing to hold marks.

Close ups used cable driven puppets for eyelids, nostrils, and mouths. Operators stood just off frame or under the set floor, and camera framing favored angles that hid support rods. Footstep impressions were created with pneumatic bladders under mud plates that could sink on cue, and practical rain gave the creatures a consistent surface highlight.

‘The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring’ (2001)

Forced perspective rigs let actors of different heights share moving shots without digital resizing. Tables and walls were built on motorized platforms that shifted in sync with the camera so perspective lines stayed correct as the lens moved. Duplicate props at multiple scales allowed actors to interact with objects that matched their apparent size.

Makeup and costume departments provided scale cues like seam width and fabric weave that read differently at close range. On set teams tracked lens choices, distances, and platform offsets in detailed logs so matching shots could be repeated across days and units. This paperwork kept continuity tight as the production jumped between locations.

‘The Dark Knight’ (2008)

The semi truck flip used a real vehicle fitted with a buried ram that fired to lift the trailer and rotate the rig onto its nose. The effect was tested at a lower speed to confirm trajectory and then repeated on the main unit street with controlled traffic lockups. High speed coverage captured the moment from multiple angles for editorial flexibility.

The hospital demolition took place in a condemned building dressed as a clinic. Charges were sequenced so the structure fell in controllable sections, and the lead actor’s path was plotted with safety officers to keep clear zones open during the walk. Practical dust and debris covered nearby vehicles and pavement to sell the aftermath in the same setup.

Share the practical movie magic you would add to this list in the comments.